If the West Gate Bridge memorial seems to suffer from a desire to downplay the significance of industrial deaths, the “Vietnamese War” memorial in Sunshine is testament to an Orwellian desire to re-write history completely. It is difficult to know where to begin.

Trends in memorials to war dead have altered significantly over the decades. Increasingly, war memorials have moved away from triumphalism; glorifying statues of heroic generals and jingoistic victory arches; to imagery that is sensitive to the desolation and loss of war. Often they require us to cast our gaze downwards in sorrow rather than upwards in exaltation. Similarly, many seek to speak to the landscape in which they are situated, merging into it rather than stamping themselves on it like jackboots.

Thus, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington consists of a black polished granite wall of etched names sunk into the hillside; the wedge shape representing the partially healed scar of America’s most controversial and contested war. The polished wall resists the urge to impose a social narrative, to glorify the dead. Rather, it passively reflects back the faces of the grieving and allows them to find their own meaning among the row after row of names. While it has its critics among the right wing red necks, the veterans themselves are apparently very fond of it.

Unfortunately, Australia has never been particularly good at simple symbolism. Perhaps the best of the Australian memorials to the war in Vietnam is the Memorial Walk in Seymour. This curving wall of glass panels situated in a landscape that (theoretically) recalls the landscape of Vietnam does not aim to glorify the dead but rather to “commemorate the service of all who played their part in what turned out to be a tumultuous part of Australia’s history”, including women and dogs! The literalism evident in the images embedded in the glass is perhaps understandable given this purpose. The walls serve as the repository for random memories from those who served and while this restricts the potential social narratives available, it does not close it off entirely. Not so the Sunshine edifice.

This memorial has less to do with grieving for dead Australian soldiers than glorifying dead South Vietnamese generals. The Australian involvement provides a mere fig leaf to this end. The central flag waving pillar proclaims on one side, “In memory of 521 Australians who died defending the Republic of Vietnam”. Apparently the definite article was not considered necessary. Perhaps the dying is not over yet! As for “died defending the Republic of Vietnam”, this might be how some of the South Vietnamese saw the issue, but I think the official ‘truth’ is that they died defending Australia’s alliance with America. Australia would not have been in Vietnam otherwise and in fact was never officially an ally to the Republic of Vietnam. It would also be correct of course to say, “they died in the service of their country”. An open expression such as this would at least have had the virtue of not imposing a highly politicised social narrative on the viewer.

The reverse side of this unfortunate jutting edifice displays in the colours of the now non-existent Republic of (South) Vietnam (actually the flag of the last ruling emperor), tiles proclaiming something to the effect, “Those who died for the father land”, topped by “For the Unknown” in large font English and at the bottom in smaller font, “[The] military and official personnel [of the] Republic of Vietnam and its allies”. While I have no doubt there were many anonymous military personnel who “died for the father land”, in its totality the inscription certainly lacks the ecumencal, “known unto God”, and equally, it lacks the inclusivness of Keating’s “He is all of them. And he is one of us.” Rather than heal the scars of war by acknowleding the dead are equal in death, this monument seeks to continue the divisions of this particular war.

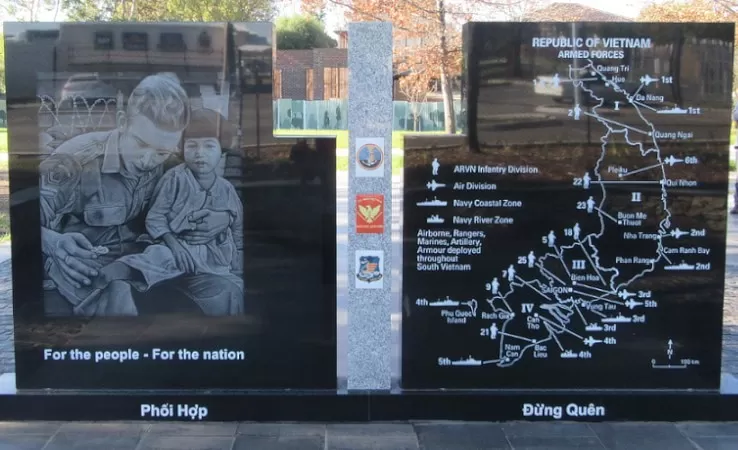

However, the central pillar pales in relation to the real offence here; the accompanying panels on either side. Despite the truly pointless listing of Australian names and the school book illustrations of geographical locations of battles, the reverse side of these panels aim to glorify a very particular view of history. There are echoes of American propaganda. Obliging GIs giving gum to cute children are replaced with a soldier apparently tending to an equally cute child’s stubbed toe. No interpretations needed here. No complications of torturing prisoners or razing villages or shooting Buddhists, or supporting colonialist occupiers or… . Nothing complicated here. Oddly, this image also appears on the Seymour moment but at least there it decently acknowledges the photographer, here the concept of plagiarism is unknown. Likewise, the map showing the many places the ARVN fought and the (highly dubious) time line that omits any reference to French occupation, religious sectarianism, civil war or the peace movement in the West. While all attempts at the narrative of history must inevitably omit as much as they include, the partisan nature of this monument is gob-smacking. This, according to those unveiling the edifice, was the “true story of the Vietnam war”.

To reinforce this very particular version of history, the monument also includes a series of plinth-like blocks with the images of five ARVN generals, all of whom committed suicide rather than confront the collapse of the South and the victory of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. It is unclear why images were considered appropriate, where these images came from or why these particular ones were chosen. Presumably, this is some attempt at maintaining the cult of the heroic warrior. Unfortunately, in the case of Major General Nguyen Khoa Nam, it has succeeded only in making him look like a kind of Mafia thug.

In any case, these are not the suicide sacrifices that spring to my mind in association with the Vietnam war. The image that is seared into my version of history is Thích Quảng Đức immolating himself to protest the treatment of Buddhists at the hands of the Diem government, the same government that acquired power with the help of the CIA, the same Ngo Dinh Diem who was a collaborator with the Japanese occupying forces during WWII. The same Ngo Dinh Diem who is merely listed here as “elected president”, a phrase utterly replete with ambiguity.

No doubt there are many members of the local Vietnamese community who honestly believe that that this edifice pays homage to those who died “protecting the Vietnamese people for Communism”. The virulent anti-communist and anti Socialist Republic of Vietnam attitude of the local Vietnamese language media and the political opportunism of those who have facilitated the creation of “little Saigon” is worthy of a PHD dissertation. There is however, no excuse for the utter insensitivity of this war memorial. Not only does it offend the Buddhist community, it excludes any other possible interpretation of this turbulent moment in history. It imposes a social narrative that grossly offends many hundreds of thousands of Australians who thought Australian forces should never have been in Vietnam. And I am one of them.

Even the enemy are entitled to mourn their dead but they are not entitled to rewrite history.

For those interested in further reading:

https://blogs.crikey.com.au/theurbanist/2013/04/24/designing-war-memorials-is-simple-best/